Business succession for a long-established company

– the path we have chosen

Orbray's Future, Vol.6

On January 1, 2023, we changed the name of our company,

Adamant Namiki Precision Jewel Co., Ltd., to Orbray Co., Ltd.

Today, I am going to discuss how I and Executive Vice President Osamu Wada have come to take the helm of our company’s management.

For over 80 years, Adamant Namiki Precision Jewel Co., Ltd. was led by the founding president and the second-generation president, both of whom had a passion for manufacturing. However, from 2015, the company’s performance began to deteriorate, and so management decided to engage consultants to help turn the business around.

When Shoji Namiki, who was the second-generation president and my father, decided to retire from management once and for all, he named me to head the company. Though being a member of the founding family, I had never imagined that I would someday lead the firm, because I had a vocation as a professional athlete and an educator focusing on nature experiences for children.

I suspect that many people might have felt uneasy about my inauguration as president. Even so, after careful consideration and much discussion with my father, I made up my mind to take the role because I thought that the rebuilding of the company should be done by our founding family, and that we should take every step to achieve that goal even if we had to tap our private assets. I concluded that I would be the only person who could complete the mission.

Under the new management structure, we decided to return to our company’s founding philosophy – one company, one family – and as the president, I took responsibility for prioritizing employees’ well-being. We asked Mr. Wada, who initially came to our company as a consultant, to manage the business because he had successfully guided Namiki’s efforts to achieve a V-shaped recovery in financial performance.

Now, I would like to ask Executive Vice President Wada why he decided to join our company and what kind of vision he has for the firm’s future.

From consultant to executive vice president - why he chose to join Orbray

Namiki: You have provided business consultation services to more than 100 companies and been highly acclaimed for your management skills. In the first and second years with us, you earned our employees’ trust, and we strongly hoped that you would participate more fully in our company, though we weren’t confident whether you would accept a job offer. You also received offers from companies that were much bigger than us and offered bigger salaries. Why did you choose us?

Wada: I thought large companies could manage themselves without me but I was needed by Adamant Namiki. Actually, your earnest desire to improve the company and honesty about your lack of experience made me realize that the best way to assist businesses is by helping stakeholders to gain further skills and insights, paving the way for long-term success. I also believed that helping the company change over the long term from the inside as a stakeholder would give me far more satisfaction than making large, fast changes to a company and then moving on to the next project. That is why I took this job.

Namiki: We also heard that your decision to change your job to a mid-sized manufacturer’s executive vice president from a business consultant astounded bankers who knew you.

Wada: After graduating from university in 2000, I joined a major Japanese commercial bank and worked for its corporate sales department. In those days, the Japanese economy was in bad shape, and many of my corporate clients became insolvent and went out of business. I wanted to provide in-depth support to them. So, I left the bank and became a business consultant. As a consultant, I handled a variety of cases – including the restructuring of a big firm that had covered up scandals and exacerbated its problems; the drastic overhaul of a mid-sized company that had caused a nationwide scandal due to a lack of governance; the revamping of companies that struggled with deteriorating performance; and work in financing and mergers and acquisitions in Japan as well as abroad.

Namiki: You came to our company as a consultant at first. In those days, we were hard up for a solution because many experienced workers had quit en masse, and we were bleeding red ink.

Wada: My consulting team was assigned to Namiki in 2017 to turn around its business by teaming up with your father, Shoji Namiki, who was then the president. We had less than six months to complete our restructuring, which would usually take two to three years.

The first challenge for us was to push forward the integration of the two companies – Adamant Co., Ltd., and Namiki Precision Jewel Co., Ltd., into Adamant Namiki Precision Jewel Co., Ltd. – while we forged ahead with reforms of the companies’ five main businesses. We needed to close or scale down multiple sites in Japan and abroad, and let go of 20-30 percent of the total workforce, or about 600-700 workers. The process of streamlining offices and factories included the unification of the two companies’ headquarters and closures of some domestic and overseas sites. This process took a huge amount of work, which included nearly nonstop discussions with all the relevant stakeholders. We also reviewed the management structure and cut salaries of our executives as a way for management to take responsibility.

Namiki: Under the business circumstances and time constraint, what did you try to prioritize?

Wada: In such a pressing environment, stakeholders from a variety of positions voiced different opinions and requests. As our priority, we tried to help those stakeholders understand each other and stay on the same page so that we could all proceed in the same direction and keep within the time limit.

Namiki: I heard that you sometimes stayed overnight in the office because you had no time to go home to sleep. You sought the participation of all employees and painstakingly listened to everyone, thereby earning their trust, which led to the achievement of the companies’ integration and their complete overhaul, to the satisfaction of both management and, importantly, all employees.

Wada: We also received inquiries about Adamant Namiki’s future from our clients outside the company. We had to carefully explain the situation and conduct negotiations with the main banks and stockholders. Above all, we gave top priority to keeping employees updated, because the direction and course of the company’s transformation were certainly a major concern for them.

With the assistance of more than 100 employees, we carried on restructuring during those six months. As Namiki had been an organization with a cozy atmosphere, I didn’t feel it too difficult to push forward with the changes.

In the business year ended in December 2018, the company reported a consolidated operating profit of 1 billion yen (about $7.5 million), a huge improvement from a loss of 2 billion yen the year before: We achieved a V-shaped recovery. Around that time, your father asked me to assist you, as he was preparing to let you succeed him as president. I believed that returning to profit wouldn’t mean the end of the company’s rehabilitation efforts, and I wanted to make a further commitment to the company to ensure continued improvement. So, I decided to accept the job offer.

Orbray's advantages revealed through management reform and reactions to the pandemic

Namiki: That was the period when the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread, wasn’t it?

Wada: We received fewer orders from clients and started to worry about the business outlook. Even so, we tried to focus on presenting our plans for the coming years. However, we forecast a loss in the future and therefore implemented measures to cope with the environment. As a result, we succeeded in returning to profit for 2020.

At the onset of the pandemic, we also embarked on work-style reform. Though we had many employees who preferred face-to-face meetings to online meetings, we increased work-from-home capabilities and cut down on business trips. We strived to raise productivity by changing workers’ mindsets.

Namiki: The pandemic has prevented us from delivering our company’s policy messages directly to employees. As an alternative, we regularly send video messages to all employees to allay any fears and foster a sense of unity. The pandemic has had the positive impact of accelerating our restructuring.

Wada: I had long considered Adamant Namiki’s factories to be well organized in terms of operations, the management of quality/cost/delivery, the allocation of functions to each department, process design, the frictionless flow from prototype to mass production, and what we call in Japanese “kaizen” (improvement) activities. Our company achieved a V-shaped recovery of business performance within only one year because all workers on the production sites worked hard to fulfill their duties. They were amazing. By working with them, I came to realize that the first and second presidents had trained up excellent workers on the production sites over a long period of time.

Namiki: We have many employees with warm personalities. In particular, the northeastern region of Japan, where we have manufacturing facilities, is the cradle of unpretentious, meticulous people who make excellent craftsmen. In contrast, we base our sales headquarters in Tokyo to utilize the skills of outgoing people who are knowledgeable about international business. I believe this is a well-balanced structure.

Wada: In addition to its workers, another of Adamant Namiki’s competitive advantages is its technology. The company comprises an aggregate of business departments, each of which has dozens of niche technologies. Each department manufactures a variety of customized products, which is possible only with Adamant Namiki’s production facilities and tools, its expertise in customization, and other proprietary in-house capabilities. Few other companies can match Adamant Namiki’s strengths.

Adamant Namiki is also a non-keiretsu (non-affiliated), independent manufacturer that has a large number of small clients. This is rare for Japanese manufacturers. We are less dependent on just a few large clients – another of Adamant Namiki’s advantages.

Orbray's initiatives to change corporate culture - listening to individual employees

Namiki: We are really fortunate to have good clients. Without our bold restructuring, we could have gone bankrupt and left those clients deprived of our design and manufacturing support.

Wada: One of the things I noticed was that the company had maintained what was initiated by the first and second presidents – and failed to keep up with the changing times. There had been some upgrading in certain areas even before the integration of the two companies– business portfolio management, management structure, overall organization, conference bodies, and computer systems. However, I thought the company desperately needed improvement of the corporate culture. For example, it is not acceptable to young workers nowadays if their more senior workers say: “Please get this done by tomorrow. You can do it, can’t you?” At Adamant Namiki, such heavy-handed bossiness was observed frequently. Some young workers felt discouraged from making proposals because they thought their opinions would never be heard. Also, the company often asked employees to work on weekends. Managers used to believe that it was the workers’ duty to be on shift on Saturdays and other holidays every few weeks to keep the machines working. We have considerably reduced such shifts in recent years, but old habits die hard in some sections.

Namiki: We need to take some action to increase the number of female managers. Few women hold such positions at the moment. In June, we held a self-development seminar targeted at female employees. Currently, it’s not easy for them to publicly express their aspirations for managerial positions, so we try to encourage all employees to step up their careers. By doing this, I hope to encourage female workers to have a greater commitment to our company.

Wada: Narrowing the generation gap is also one of our challenges. Employees in their twenties account for less than 10 percent of the total workforce, while those in their fifties and sixties make up 30-40 percent. One reason is that when young workers make a proposal for improvement, their seniors are prone to resist because they don’t understand why it’s necessary to change what has been done for years. Senior workers tend to regard younger workers’ suggestions as just complaints. When I reprimanded a senior employee for making remarks that sounded inappropriate to me, other employees in the same generation spoke up for him, saying he wasn’t wrong. To be sure, we should respect the contributions and efforts that senior staff members have made for the company, but we also have to adapt to a new environment.

Namiki: If we knew each other better, we would be more willing to help each other. To that end, I do an individual interview with each employee. It’s important to offer them an opportunity to speak frankly in a meeting with the president. As a result, I think the atmosphere in our office is gradually changing.

Wada: Until recently, each department had little communication with other departments, so they knew little about each other. It’s necessary to communicate with the other departments to build a comprehensive understanding throughout the company.

Namiki: In addition to individual interviews, I also conduct interviews with groups of 10-20 employees. They explain to me what they do and this is published in our in-house magazine. We also put up a photo of each employee. This makes it easier for workers at other departments to speak to him or her. We hold a gathering of employees with the same birthday month and I give a birthday card to each person. Just after I started the group interviews, I was the only speaker while everyone else remained quiet, but people have recently begun to speak up. The other day I was asked what kind of president I would like to be. I replied that I want to build a relationship like a family, which allows us to think and talk intimately.

Wada: Every day, I try to listen to employees’ voices when they arrive at and leave the factories. I feel their voices sound livelier than before.

Making unique products that benefit human life - securing the future for Orbray and Japan's manufacturers

Namiki: I would now like to talk about Orbray’s future. The first and second presidents had charisma, and they expanded the company’s business through top-down management. From now on, I would like to shift to bottom-up management that focuses on communication with staff members at production sites and listens to their opinions. This approach would also respect technology and empower human resources to enable workers to keep learning within the company. Specifically, I would like to enhance training and education for employees to deepen their engagement.

Meanwhile, I want to preserve the company’s ownership by our founding family. I believe that ownership by the founding family is the most powerful and sustainable business model for a corporation. I regard myself as a middle relief pitcher in baseball, and my mission is to pass the game on to the next pitcher. By conveying this notion to the next generation, I intend to build a company that can survive for hundreds of years.

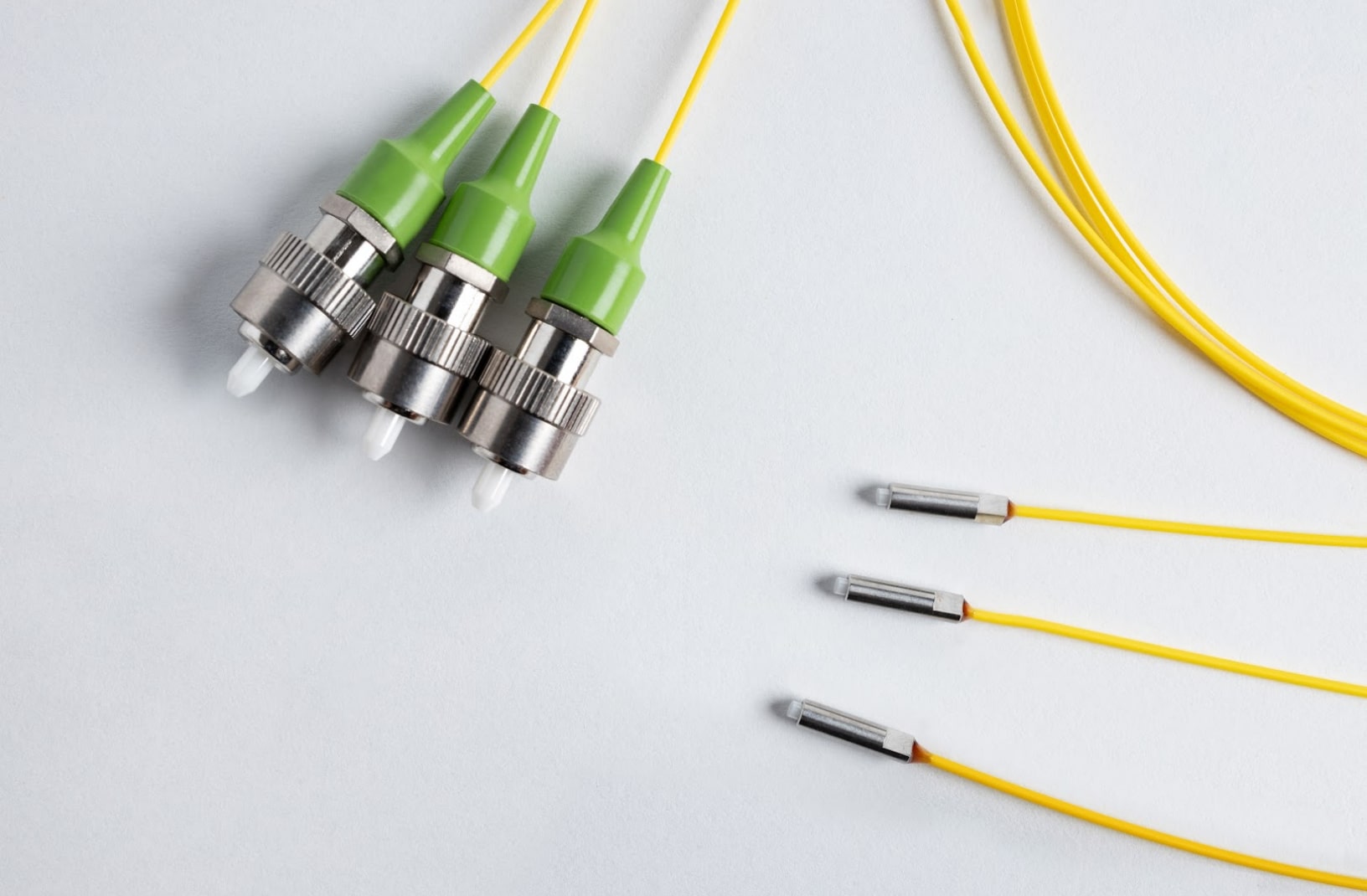

Wada: Our company has five businesses: photonics, precision jewels, motors, medical equipment development, and specialty diamond products. We have no plans to change this business portfolio. Our performance is in a pretty good shape now and we project 25 billion yen in sales and 4 billion yen in operating profit for the current fiscal year ending December 31, 2022. Two years ago, our sales were 14.4 billion yen and operating profit totaled 200 million yen. Net assets, an indicator of the company’s financial soundness, are projected to reach 12 billion yen at the end of the current fiscal year. We will probably need no changes to the basic blueprint for each business for now, though there may be some minor adjustments if needed.

Namiki: We want to put more focus on one business than the other four, however.

Wada: Yes, that’s medical equipment. All of the five businesses have something to do with the medical field – we have a varied product line-up, such as infusion pumps, small motors for surgical instruments, and dental blocks made of zirconia. Sales from medical equipment have grown rapidly over the past few years, and we expect sales from this business to exceed 10 billion yen for the current fiscal year, compared with the projected 25 billion yen for total sales. While the communications and semiconductor businesses, which are the mainstay of our company’s sales, are subject to the economy’s ups and downs, the medical business is more resilient, and we expect it to grow steadily in the future. The medical business requires precision manufacturing and products of the highest quality, similar to precision equipment, which is our main product. Our strategy is for medical equipment sales to keep increasing to account for more than half of our total sales, to ensure more stable profits.

Medical infusion pumps used to be marketed by another global company, for which we were the subcontractor. When the maker decided to pull out of the business, Shoji Namiki, the second president, purchased the business. At the time, he faced opposition from his employees, who said it was beyond Adamant Namiki’s capacity. However, the president managed to persuade them, saying the company should take decisive action to survive.

We must assume that domestic sales in Japan will decline as the country’s population keeps shrinking. We need to boost the ratio of overseas sales. At the moment, our overseas sales are on track to total a little more than 12-13 billion yen for the year. Recent depreciation of the yen will likely boost our overseas sales further, particularly those in the U.S. and Europe.

Namiki: I want to emphasize the importance of human resources. Against the backdrop of our corporate philosophy of “one company, one family,” I want to improve employees’ benefits and enhance the working environment to encourage greater commitment to the company.

It’s also important to hire young workers and help them stay with us as long as possible. I want to create a company that employees want their children to join.

We don’t need to achieve sales of hundreds of billions of yen. But I want our company to continue for 100 years, or even hundreds of years. I want our company to report 30-40 billion yen in consolidated sales and 3-4 billion yen in operating profit per year, consistently. We aim to be a global leader in niche markets for our company’s businesses. Taking advantage of our creativity and perseverance in taking a product from concept to market, we strive to manufacture products that benefit human life and that you can’t find anywhere else in the world.

Wada: Over the past two to three decades, Japanese companies have advanced into China and ASEAN nations and opened factories there. While supporting those moves as a business consultant, I now believe that Japan has been neglecting the importance of domestic manufacturing facilities, and I feel embarrassed now that the shoe is on the other foot.

Still, we have observed some changes in the offshoring trend in recent years. China and ASEAN countries are starting to change their manufacturing-centric economic policies. Reflecting upon how the pandemic has disturbed the production and distribution of semiconductors and other parts, causing shortages, Japanese companies have come to realize that they need to keep some production at home, rather than just pursuing cost-cutting efforts. The yen’s depreciation is adding momentum to such changes in strategy. I don’t think this is a temporary change. I anticipate that companies all over Japan will shift production back home from overseas over the next five to 10 years at an accelerating pace. I am looking forward to seeing further development of Japan’s manufacturing industry.

At our company, we will also continue our efforts to improve wages and working conditions for both permanent and non-permanent employees.

Namiki: Recently I have had more and more opportunities to meet second- and third-generation presidents of Japanese manufacturers. There is only so much that our company alone can do. Therefore, I want to join hands with these other companies and make an advance into the global market in an “all-Japan” effort to expand the brand recognition and global client base of each company. I want all Japanese manufacturers to thrive.