Adamant Namiki’s Initiative for SDGs: Enjoy Sports with People with Disabilities

by President and CEO Riyako Namiki

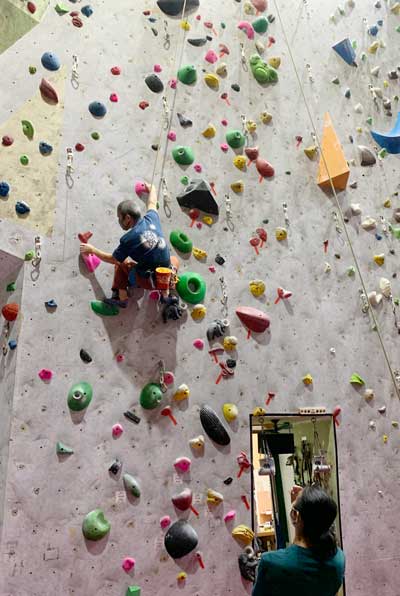

Climbing is a sport to climb up walls with colorful holds. It became an official event in the Tokyo Olympic Games in 2021 and Japanese athletes performed very well. I believe many spectators were impressed by the athletes’ actions of supporting their entire weights only by fingertips and toes and climbing up vertical walls swiftly to trace small holds.

When I lived in the United States, I tried out the sport. However, I didn’t know about a paraclimbing until Naohisa Hatakeyama, who’s my friend and a wheelchair user, invited me to a meetup of players.

According to Koichiro Kobayashi, who’s a top paraclimber with visual impairment and the head of NPO Monkey Magic, the organization started as a body to support exclusively paraclimbers with visual impairment but has gradually included those with hearing disability, limb deficiencies and paralysis, development disability as well as wheelchair users. Currently, players ranging from small children to those in their seventies participate in a gathering.

“Climbing is a sport that everyone can enjoy at the same place, under the same rules. Those who have sight impairment can also enjoy it with a little help,” Kobayashi said. NPO Monkey Magic hosts a gathering.

Visually-impaired climbers can’t see where holds are located on walls and what colors they are. Holds are painted in vivid colors because colors indicate which protrusions athletes are allowed to grab during climbing, depending on their performance level. Sight-impaired athletes can’t see them. So, a sight guide is assigned to each paraclimber to give instructions. At NPO Monkey Magic, a support from a sight guide is provided in the words of H (‘houkou’ – direction), K (‘kyori’ -distance) and K (‘katachi’ – shape.) In the gymnasium, we can hear vigorous spoken instructions such as “in the 11 o’clock direction, far-away, a banana!” The venue was full of vigor and performers looked very lively.

A sight guide tells a paraclimber in which direction a hold is located and how far it is, and in what kind of shape it is. They don’t give any more tips. A climber needs to consider which arm should be used to grab a hold and which leg should be used to step on. A climber must think and use imagination and decide how to move his or her limbs. Otherwise they would become no more than puppets.

A sight guide keeps giving instructions to prevent a paraclimber from feeling uneasy. I tried to play the role of a sight guide. Giving instructions was more difficult than I had expected and I was convinced that it is important to build a trust between a climber and a supporter.

A visually-impaired female paraclimber, who is a 10-year veteran of the sport, said that players must use both body and brain. “We can master the sport only if we use both body and brain – that’s a real thrill of paraclimbing,’’ she said. Ryota Hirai, a wheel-chair user and an 18-month veteran of the sport, said he can feel a sense of accomplishment when he gets to be able to do what he couldn’t do before. “Though I have a progressive intractable disease, I keep challenging day by day,” he said firmly. Hirai wants to work for a training gym and hopes that more athletic facilities will become wheelchair-friendly. His comment leads me to wonder how many gyms can cater to the needs of those who have disabilities. I hope people with disabilities can feel free to enjoy sports as they are prone to have a lack of exercise.

Hatakeyama, who represents Japan at paraclimbing and invited me to the gathering, is a watch-repairman on wheelchair and a long-time friend of mine. Every time we meet, we always have fun talking about what he has challenged. He has conquered all steep slopes in Tokyo on a wheel chair, but this is just a tip of an iceberg of his adventures. I was astonished with his fortitude when I heard that he succeeded in doing a front hip circle on an iron bar in the park while being on a wheel-chair.

Kobayashi of NPO Monkey Magic lost his eyesight because of pigmentary degeneration of the retina after he became an adult. He said he had been always worried about which ability he would lose next as his disease got worse. A case worker told him: “We can’t help you as long as you keep worrying what you would become incapable of doing next. There are more important things you should think about – what you really want to do and what kind of life you want to live. If we can find those clues, people around you like us and our society can offer a support to you.’’ These words changed his mind in a positive manner and he started to think about what he can do. The website of NPO Monkey Magic says: “You can go over a wall even if it is invisible.”

Hatakeyama said he had often felt unsure about what to do when he had no disabilities because he had a full range of choices. “However, once I have become impaired and had only 10 percent of choices, I have little room to hesitate. This is my life and I can’t shift blames to others. I must make a choice and take the responsibility of my decision. To be sure, I wish I could get back what I have lost, but it may sometimes work better if I give up gracefully,” Hatakeyama said.

In the past, Kobayashi said in an interview: “All people have something they can do and they can hardly do. I am 5 feet 2 inches tall and can’t reach some holds on the wall, which taller people can reach. Some people are strong and some are weak. If we think this way, I wonder what disabilities are.”

What a positive and flexible thinking! I have never cared about people’s appearances, abilities and whether they have any disabilities or not. Rather, I appreciate the opportunities of noticing something that I, an able-bodied person, can never realize for myself.

Turning my eyes to our company, I can see each employee has his and her strong and weak points. It’s important to accept them and cooperate to support each other – this is a lesson I have learned from the gathering where I saw para-athletes climbing up walls with the assistance from able-bodied supporters.

To be honest with you, I am an acrophobia and I hate to get onto a lift and a gondola in ski fields. However, to my surprise, I felt no fear and completed a wall climbing at the event. Probably, other participants’ powerful performance encouraged me. Next time, I would like to challenge a climbing with a blindfold.

-

Adamant Namiki’s Initiative for SDGs – Launching ‘’fro-pro’’ Workshop

-

Adamant Namiki’s Initiative for SDGs: Final Presentation Meeting on ‘Fro-pro’

-

Roundtable Discussion with Narutec

-

My speech at Kuroishi High School – Realizing Our Dreams through Courage and Effort

-

Islander Summit Ishigaki – to Reflect on SDGs from Global Perspective

-

Two Teams Go All Out in the Koma Taisen Akita Tournament!